Gowanus Wild: A Conversation with Miska Draskoczy

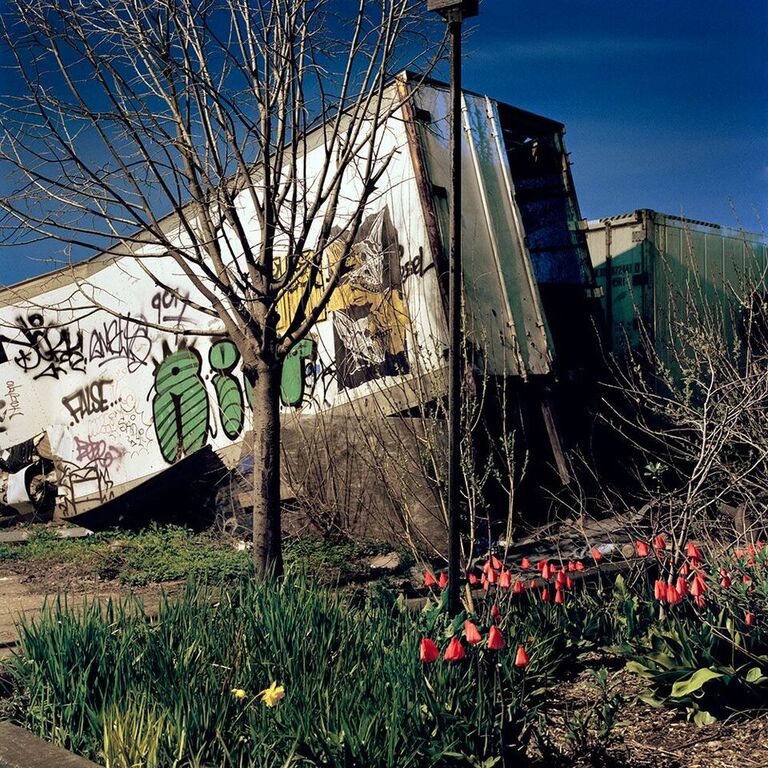

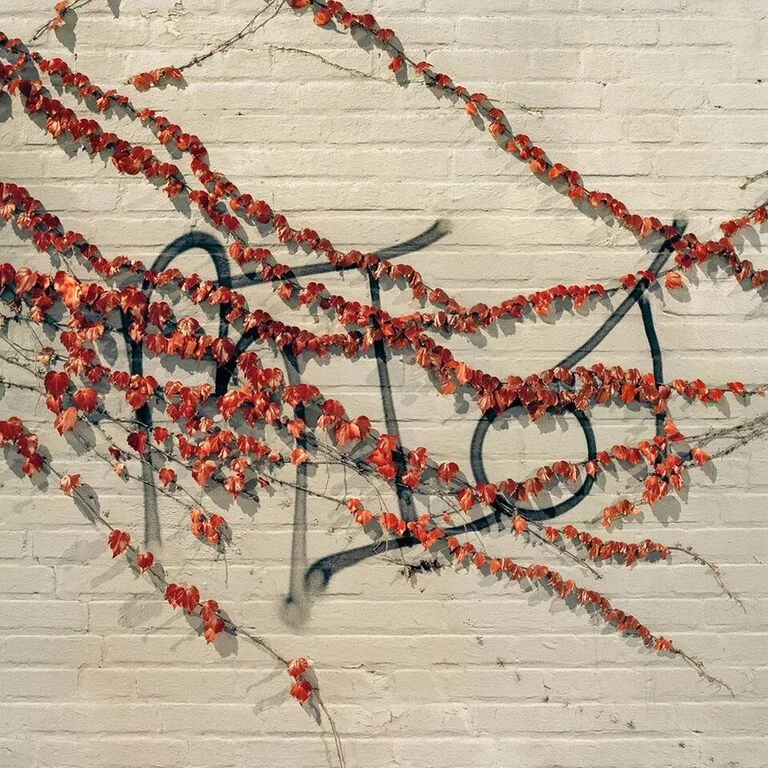

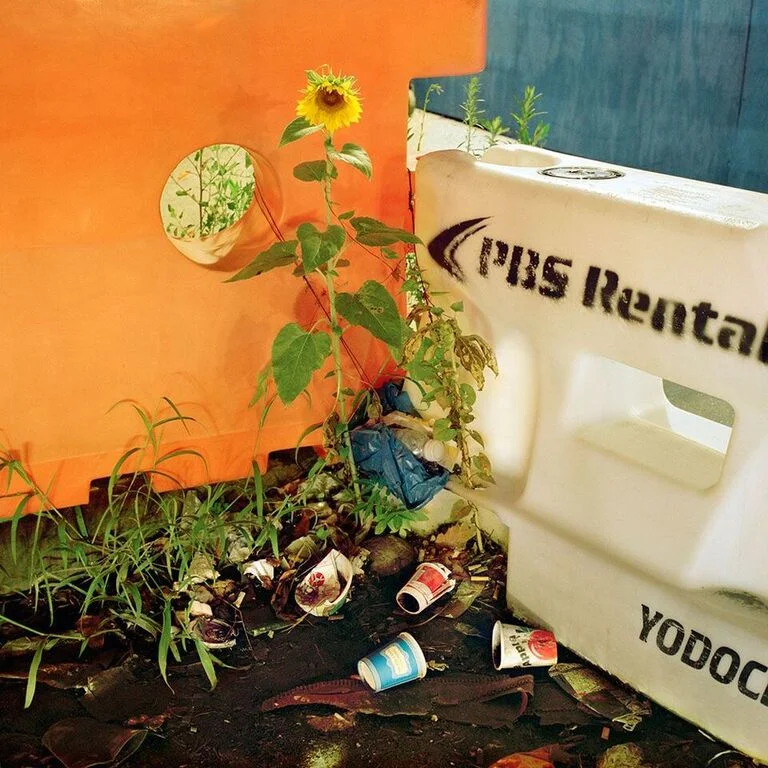

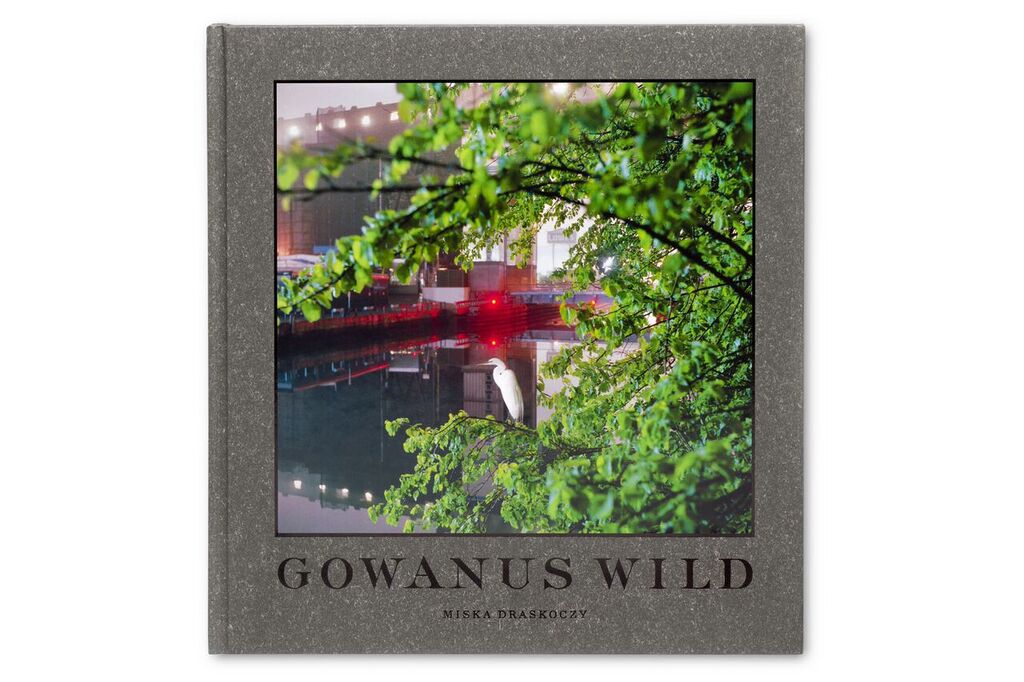

I was all in the second I came across photographer Miska Draskoczy’s Kickstarter campaign to support Gowanus Wild (https://gowanuswildbook.com), a book of photographs exploring nature and wilderness in the Gowanus Canal, our beloved Superfund site. So I ponied up $50 to help Draskoczy get his project off the ground (and secure a signed hardcover copy as my bounty). Eleven months later, I was rewarded with a stunning coffee table book filled with spooky, beautiful images of the Gowanus. Devoid of human beings, the photos nonetheless vibrate with life. Saturated with color and suffused with spirit, they capture how nature finds a way, even in the most hostile environments. My favorite is a sunflower bursting forth from the poisoned loam beneath two plastic Jersey barriers, like Ginsburg’s “Sunflower Sutra.”

In truth, I supported the project because I knew the weird, sketchy, slightly dangerous, and oddly beautiful neighborhood that BCL moved into back in 2009 was changing quickly, and I wanted someone to record what had been left behind, or built over. Draskoczy’s photos–shot from 2012 to 2013–capture a Gowanus that has vanished before our eyes. (Of the 57 locations in the book, Draskoczy estimates that over half are no longer there.) But change is an implacable force in this city. For better and for worse, change gives the the city its protean energy, fueling the fire of reinvention that has drawn artists, hucksters, and strivers to the city since the days of Breukelen.

We sat down with Draskoczy recently to talk about his book, the urban environment, and a changing Gowanus. The interview was edited for length and clarity.

-Neil Carlson, BCL Cofounder

BCL: Tell me a little bit about yourself. How long have you lived in New York? Where do you live now?

MD: I live on the Gowanus-Park Slope border. But I’ve lived in New York since 1999, so 18 years. Chinatown for 10 years and now Brooklyn for eight. There’s always another move.

BCL: And how did you come up with the idea for Gowanus Wild?

MD:I moved to the Gowanus area in 2008, in large part because it’s a great place to park, strange as that may sound. Like many in Park Slope, I’ve often found it easier to park in Gowanus, and Gowanus at the time was extremely dead. So I was always walking around late at night.

It was a weird time because when I moved here there was no indication that Gowanus was going to change anytime soon. It was just this out-of-the-way, sketchy industrial area that no one really gave a second thought to. And by all indications that wasn’t going to change, at least if you didn’t know what was going on behind the scenes.

My creative output up to that time had been primarily as a filmmaker, but I had been shooting still photography for my own personal projects for years and then this just kind of bubbled to the surface. It was the first major still photography project I threw myself into. At first, I was just taking pictures around the neighborhood because it was this kind of eerie and bizarre place. But then I started noticing that it was surprisingly wild.There were blooming flowers and trees, weird little plants, and of course the canal itself. This defiant nature was the thread that tied things together for me, especially in a neighborhood famed for its toxic contamination. I’ve always been into hiking and backpacking, but I started getting more into rock and ice climbing at the time. So I was spending a lot of time out of the city, and I feel like these two things in my life kind of blended together in Gowanus. It became my urban nature experience.

© Miska Draskoczy

BCL: Do you feel like being out in nature — backpacking, rock climbing, all of that — gave you a greater sensitivity for nature in this urban environment?

MD: Definitely. When I first moved to New York, I would go on endless bike rides with friends, things like riding the length of Staten Island or all the way out to City Island. So having outdoor adventures in the city was a familiar thing to me. But it was totally different to shoot at night. The streets were vacant, so my wanderings became these meditative, solo quests. I’d go out from midnight until four in the morning. The only people out were garbage haulers and prostitutes.

BCL: How did you choose your subjects?

MD: Spring 2012 is when I started shooting, but it went in fits and starts. I’d shoot for a month or two, and then, frankly, just get busy. I was freelancing in film and television in post-production, and I’d go through through periods where I was working long hours every day and I didn’t have time to shoot.

The other big challenge was finding the internal logic of the project. It’s like I start off with an inkling of where I’m headed but I have to figure out what the rules of the game are, so to speak. Once I realized that my theme was nature, it was like, “Alright, now how can I find every example of nature in Gowanus? Is it water? Sky? Earth? Plants? Is it a wide shot? A close up?” Eventually, I brought a filmmaking mentality to it, like, “I want to have a shot list and then go out and get all the different shots.”

BCL: So, did you make a shot list as you were going through?

MD:Yeah, I think it helps to go out with a laundry list of the things you want to keep an eye out for, but knowing you may not find them. Blooming flowers are only out for about two weeks, so you have to show up then. Nature gives us a narrow window sometimes. Likewise, anytime there was a huge blizzard I would clear my schedule and head out for the day. But shooting in a blizzard has its downsides as well.

BCL: Yeah, it’s freezing cold and there’s two feet of snow on the ground!

MD: No, it’s the wind! The wind! Because everything is long exposure at night–like 8 to 15 seconds or more. A little bit of wiggle can sometimes add an interesting element to a plant but more often it would just ruin the shot. I started becoming really attuned to my outdoor surroundings. I’d walk out of the subway and think: Is it blowing constantly? Intermittently? Can I sneak in a shot between gusts?

BCL: I want to come back to something you said earlier about the flowers only blooming for a couple weeks. One of the themes I see in this project is this idea of change and impermanence. It’s almost like the neighborhood is one of those Tibetan sand mandalas, a literal manifestation of impermanence.

MD: Totally. When I started shooting in 2012, nothing had changed much since I moved here four years earlier. The gentrification aspect wasn’t on my radar screen at all. Then, as I was wrapping up in late 2013, Whole Foods opened–and the floodgates were released. Late 2013 into 2014, that’s when there was this huge sea change. All of a sudden you’d see people pushing baby strollers over the bridges at midnight. You’d never see that before.

© Miska Draskoczy

BCL: So how have you seen it change? Are there specific things you can point to as markers of that change?

MD: Well here’s one: I went through the book the other day, just to see how much had changed, and I’d say over 60% of the images either don’t exist anymore or are heavily altered.

BCL: Wow.

MD: Yeah.

BCL: Wow.

MD: Yeah, so, that’s the crazy part. The series has suddenly become this historic record far, far sooner than I ever thought.

BCL: That’s surprising to hear because the photographs themselves, just by the way you shot them, seem very elegiac, right? Do you feel a sense of loss about the neighborhood?

MD: I definitely did at first, but now I don’t know. I feel like, one, I’m getting used to it. The human brain just naturally tends to adapt. And, two, I feel like…you know, it sounds like a heavy question in a way, but what does it really mean to be a New Yorker? If you’ve lived here for a while or if you’re a native, does New York mean ‘classic New York’? Is it old school Brooklyn neighborhoods? On the other hand, the reason I came to New York is because it’s all about change. And that’s precisely what makes this city so great. Am I thrilled about all the changes and the gentrification? No, not really. But, I also have to admit that some of my friends now live in the new condos going up. I can’t just throw it all under the bus and say, “Oh, yeah, this is the real New York, and this is the fake New York.” Instead I feel like I have to accept that New York is this huge collage of people, cultures and forces that’s constantly changing, and that by moving here, or choosing to stay, you buy into that on some level.

Copies of Gowanus Wild can be purchased online from the publisher. The book is also available at Gowanus Souvenir Shop and Ground Floor Gallery, both of which are featuring a selection of prints on view through January 1st.